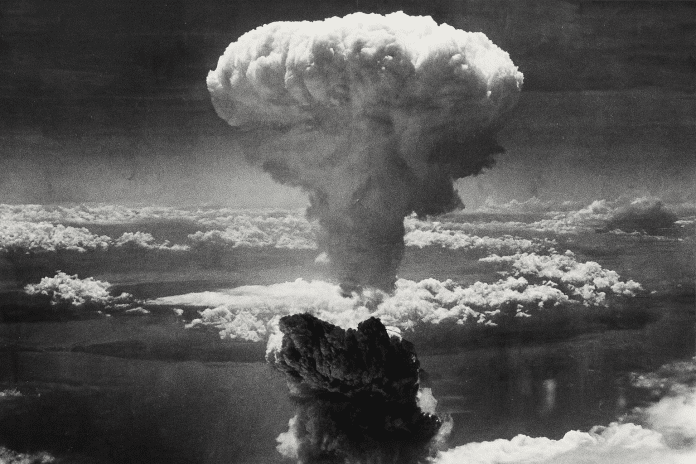

Hiroshima, Japan – Eighty years later, the world pauses this week to remember Aug. 6, 1945 — the day the United States dropped the first atomic bomb used in warfare on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, forever altering the course of history and human understanding of war.

According to historical records from the U.S. National Archives, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay released the bomb — nicknamed Little Boy — at approximately 8:15 a.m. local time. Below, Hiroshima was alive with morning activity when the blinding explosion erupted. In an instant, as many as 70,000 people were killed. Those who survived the initial blast were hit with an intense heat wave and shockwave that leveled nearly every structure within a mile. Fires swept through the city, leaving devastation in their wake.

Three days later, the U.S. dropped a second bomb, Fat Man, on the city of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 35,000–40,000 people instantly. By the end of 1945, historians estimate that about 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki had died, including those who succumbed to injuries and radiation sickness. A letter written on the day of the Hiroshima bombing by physicist Luis Alvarez, a Manhattan Project scientist who observed the mission, reflected a mix of regret and hope. He wrote of “killing and maiming thousands of Japanese civilians” but also expressed a wish that “this terrible weapon we have created may bring the countries of the world together to prevent further wars.”

The decision to use the bombs was driven by the U.S. military’s intent to end World War II quickly and avoid what was expected to be a costly invasion of Japan’s mainland. President Harry Truman had warned that failure to surrender would result in “a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.” Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, marked the war’s end.

The aftereffects, however, extended far beyond the war’s conclusion. Survivors, known as hibakusha, endured lifelong health problems, including cancers, chronic illnesses, and psychological trauma. Radiation exposure also caused long-term environmental damage.

In the decades since, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings have stood as stark reminders of the catastrophic potential of nuclear weapons. The United Nations and many nations have worked to prevent their use through agreements like the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. While global stockpiles have decreased from their Cold War peak, thousands of warheads remain. Experts warn that geopolitical tensions continue to pose a risk.

This week’s 80th anniversary is both a solemn remembrance for those lost and a cautionary reflection on a weapon that reshaped global politics and warfare. The hope voiced in 1945 — that nuclear arms might deter future wars — remains tempered by the reality that their existence continues to threaten humanity’s future.

This article was produced by a journalist and may include AI-assisted input. All content is reviewed for accuracy and fairness.

Follow us on Instagram & Facebook for more relevant new stories and SUPPORT LOCAL INDEPENDENT NEWS! Have a tip? Message us!